In How I Learned to Drive, playwright Paula Vogel introduces us to a state of otherness relegated upon a girl by an older “uncle” figure who projects his anxieties and desires upon her innocence. Peck, who married Li’l Bit’s Aunt Mary, is not a blood relative, but he is a pedophile who manipulates his relationship with young children in order to satisfy his quest for innocence and love. Through Aunt Mary’s flashbacks, Peck’s past as a World War II veteran comes to light; he is as a man who is “swimming against the tide…fighting the trouble—whatever has burrowed deeper than the scar tissue” (Vogel 45).

A man troubled by memories of death and war that he doesn’t talk about, Vogel presents us with a sympathetic lens through which to understand Peck’s pedophilia when we learn that Li’l Bit is not his first victim. In teaching fishing and driving to children he cares about, the special interest he takes in his cousin, Bobby, and in his niece, Li’l Bit, is disconcerting, because fishing and driving are both metaphors for molestation. Although it may be understandable that a man who encountered death and loss and guilt as a soldier finds comfort in sexual activities, it is difficult to digest the fact that his sexual exploits also include children who entrust him with their innocence.

In both cases, the children function as the other, mere receptacles into which Peck can deposit his troubles and anxieties so that he can sleep at night. The adult Li’l Bit acknowledges this when Peck describes the thrill of driving his first car: “The boy falls in love with the thing that bears his weight with speed” (Vogel 32). This implies the naiveté with which children assume the angst of the adults around them. Blameless, both Bobby and Li’l Bit bear the full burden of his troubles without understanding how this weight will affect them.

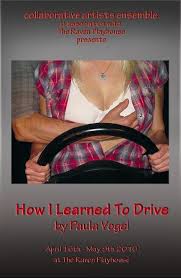

Although we do not know how the tree house incident with Cousin Peck affected Bobby, Vogel uses dark humor to explore the psychological effects of Peck’s sexualization of Li’l Bit between the ages of eleven to eighteen. Using driving as a metaphor for teaching her about sex long before she should have known anything about it, Peck discloses how he feels about women by comparing them to cars: “When you close your eyes and think of someone who responds to your touch—someone who performs just for you and gives you what you ask for—I guess I always see a ‘she’” (Vogel 35).

Peck feminizes his cars because they respond to his touch and his demands, his needs as a man who, when he drives a car, feels as though he is in control. The car is the object to his subject, just as Li’l Bit becomes the object of his desire, and a few nights a week she allows him to touch her as a man would a woman, responding to his need for power. We also see this control when she poses for him as he takes pictures he wants to publish in Playboy. Through his camera lens, she is further objectified, and in the slides on the overhead projector, the audience witnesses a combination of pictures that feature her with images of real Playboy models. By seeing her on the slides, by capturing her in a picture, Peck freezes her image so that he can look at it upon will. In pictures, he can have her, fantasize about her, and share her whenever he wants.

Interestingly, Li’l Bit asserts some power in the relationship when she calls the shots in determining where the line is drawn as to what he can do to her. But as the years progress and she feels more comfortable with his touch than she did when he first touched her breasts at the age of eleven, during which she wept, the lines keep blurring and expanding. This shows that it is not until her eighteenth birthday that she truly negotiates for power, when she builds a wall in lieu of the obscure line that stands between them. By ending their relationship, she is able to confront that what he has been doing to her is hurting her emotionally and that it has been wrong. The last scene of the play is the most powerful as she steps into her car, not into a man, and it responds to her touch. For the first time, she is in control of the car and of her life.